Heroin addiction is on the rise in the United States following an increase in prescription painkiller usage across the country.

As people become hooked on prescription opiates to manage their pain, they’re often forced to seek out heroin when the cost becomes too high to sustain their addiction.

Heroin is arguable one of the most difficult habits to shake —but with the right guidance and access to detox and rehabilitation facilities, heroin addiction can be treated successfully. Many ex-heroin users go on to live happy, healthy lives after rehabilitation treatment.

Here, we’ll discuss what makes heroin so addictive, how prescription painkiller habits often lead to heroin addiction, and what to do if someone you love becomes addicted.

We’ll also go over what a heroin overdose looks like, and what you can do to save the life of someone overdosing.

What is Heroin?

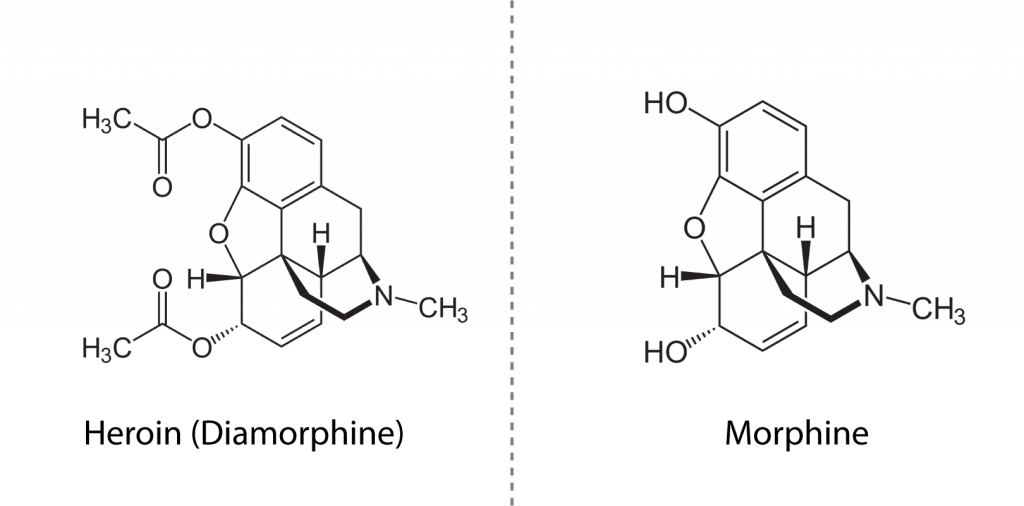

Heroin is a synthetic opiate similar in structure to morphine. There’s only a slight difference between the chemical structures of heroin (diamorphine) and morphine.

Diamorphine is roughly twice as potent as morphine [2].

Heroin produces a powerful euphoric effect when injected, smoked, or snorted. The effects can last for several hours before eventually wearing off. Long-term use of the drug can lead to widespread health issues.

Additionally, habits around injectable drugs put users at risk of contracting communicable diseases such as hepatitis C and HIV. Heroin addictions also have a profoundly negative impact on personal finances, employment status, and relationships as the drug takes a firm hold on the desires and motivations of those addicted.

Heroin becomes so addictive it can hijack our urges, habits, and desires to override all other pleasures, motivations, and responsibilities completely.

Eventually, we reach a point where nothing except finding another hit of the drug matters to us. Our health, relationships and personal responsibilities no longer register as important as seeking the next heroin high.

Street Names for Heroin Include:

- Black tar heroin

- Chiva

- China white

- Junk

- Mexican brown

- Skag

- Smack

- Horse

The History of Heroin

Heroin is one of many compounds in the opiate class of drugs.

The first opiate ever produced was opium — made by concentrating the resin secreted by the opium poppy plant (Papaver somniferum).

For centuries, opium from poppy resin was the only opiate available. Some authorities believe the first opium was made in Mesopotamia around 3400 BCE. It was popular among the ancient Egyptians and Persians as both a recreational drug, and medicine for managing pain, muscle spasms, and anxiety — much like other opiates are used today.

In 1805, chemists isolated two active compounds — morphine and codeine — from the opium poppy.

Morphine was found to be ten times more powerful than the regular opium on the market. It became crucial in the field of medicine during the American Civil war for treating pain. In the aftermath of America’s deadliest war (casualties estimated up to 800,000s), soldiers became hooked on morphine. This ultimately began the opioid epidemic still rampant throughout the country today.

In 1874, a synthetic opioid molecule was discovered by an English chemist named Charles Romley Alder Wright. This compound was heroin, at the time referred to as diamorphine.

Heroin wasn’t produced commercially until 1898 when the German pharmaceutical giant, Bayer Pharmaceuticals stepped in to manufacture the drug on a large scale with the help of another prominent chemist, Felix Hoffman — responsible for developing Aspirin.

Upon release to the market, heroin was used as a cough suppressant. It was gradually adopted into medical practice as a replacement for morphine for its stronger level of effects and the belief that it was less addictive than morphine.

Turns out this they were wrong — heroin remained highly addictive, and heroin abuse quickly became a widespread problem in the United States.

Over the next couple of years, heroin was made illegal, and morphine became the primary analgesic used in hospitals once again.

Today, Heroin is a schedule I drug in the United States. Drugs in this category are considered to have low medicinal value and a high likelihood of causing addiction.

How Heroin Works

Heroin is an opiate receptor agonist — which means it binds to and activates the opioid receptors. These receptors have a variety of different roles in the human body. This gives heroin its characteristic effects and is also what makes this drug so addictive.

What’s the Function of the Opiate Receptors in the Body?

- Control the amount of pain signal reaching the brain

- Regulate the autonomic nervous system responsible for controlling breath rate

- Regulate the release of dopamine from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the brain

- Protect the neurons from hypoxic (low-oxygen) damage

- Modulate emotions

- Stop epileptic seizures

The Effects of Heroin on the Body:

- Inhibits pain

- Stimulates feelings of euphoria

- Alleviates symptoms of anxiety and stress

- Slows breath rate

- Slows the heart rate

- Lowers blood pressure

- Causes sedation and improves sleep

What Makes Heroin Addictive?

Heroin use often starts out manageable. People take it for the euphoric high it produces. At first, they may only take it at parties or special occasions and believe their drug use is under control.

However, the drug is powerfully addictive — leading to compulsive use of the drug sooner or later. It can be impossible to control, and users often find they spiral out of control as the drug takes firm control over their routines.

But why is heroin so addictive? How is it that someone can become hooked on the drug with as little as a single dose?

The answer is in its effect profile.

Heroin, like other opiates, is an opioid receptor agonist (it activates the receptor).

When Heroin Molecules Activate the Opioid Receptors, Three Main Things Happen:

- Pain transmission heading toward the brain is stopped

- More dopamine is released into the brain — producing feelings of euphoria

- Activity in the respiratory center and several other key regions of the brain are inhibited

These effects lead to addiction in two main ways:

1. Heroin & Behavioral Addiction

Heroin brings habitual behaviors — the ritual of shooting up with friends easily forms social routines. This develops into a behavioral addiction over time as it becomes the norm to use heroin in this context.

These habits are further driven by something called the reward center — a region in the brain associated with habit formation. The reward center is regulated by dopamine and is designed to condition higher brain-regions to form beneficial habits such as eating, taking care of the body, making new social bonds, and having sex.

Normally, when we do something that benefits the body, the reward system is activated, giving us a small dose of oxytocin — a neurotransmitter that produces brief feelings of euphoria. The brain loves feeling euphoric and will try to repeat the action that resulted in this effect.

Since heroin promotes the activation of the reward center, the brain learns to crave heroin to reach that euphoria — even though this isn’t ultimately helpful to the body.

This process quickly forms routine use of the drug — if allowed to continue this will lead to physical addiction, which is much more difficult to overcome.

2. Heroin & Physical Addiction

The next form of addiction that develops — which is far worse in the long run — is a physical addiction.

This develops gradually as heroin use becomes more routine.

Heroin causes changes to the body, which push us out of balance (homeostasis). In order to keep the body within optimal levels, it starts to adapt to the heroin — making it less effective. One of the ways it does this is by hiding some of the opioid receptors throughout the body.

As this happens, we need to take higher doses of heroin to achieve the same effects. This process is called “tolerance.”

As tolerance builds, the changes the body makes become more dramatic — whenever the drug isn’t in the system, we become unable to activate these receptors with our endogenous opiates (endorphins). This is referred to as “dependence” because we start to depend on the effects of the drug to maintain balance (homeostasis).

If we stop taking the drug, or the effects of the drug wear off, the body becomes ill and can no longer keep itself in balance. This is what we refer to as “withdrawal.”

Dependence and withdrawal are the main driving factors for long-term heroin addiction. As soon as the heroin high begins to wear off and withdrawal symptoms appear and, the body feels terrible, and higher regions of the brain will crave another hit of the heroin just to feel “normal.”

By the time this is happening, drug users are no longer taking the drugs for pleasure; they need it to prevent the onset of withdrawal symptoms. Once this stage is reached, it can be tough to break the cycle of addiction without professional intervention.

What are Heroin Withdrawals?

Heroin addicts experience withdrawal symptoms as soon as the drug starts to wear off.

Even people who aren’t yet physically addicted to the drug will experience negative side-effects during as the high wears off. Withdrawal symptoms appear 6-12 hours after the last dose and can last anywhere from one to five days.

Some people can experience withdrawal symptoms up to several months. This is known as post-acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS).

If you’ve become addicted to heroin, it’s very likely that you’ll begin to experience withdrawal symptoms when you quit. Think of heroin as a loan with absurdly high-interest rates — whenever you take the drug you’re cashing out a loan. The longer this goes on for, the longer it takes to pay the loan back once you quit. You will only be able to feel normal again once the debt has been paid off in full.

Withdrawal symptoms of heroin can be severe, leading to debilitating side-effects and intense cravings.

Heroin Withdrawal Symptoms:

- Aches and pains

- Runny nose

- Nausea and vomiting

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Fevers/chills

- Cravings for more heroin

- Diarrhea

- Flu-like symptoms

Treating Heroin Addiction

There are several different treatment options for heroin addicts.

The gold standard of treatments is a detox/rehab facility where experienced medical professionals and addiction experts can monitor and support the recovery process.

There are three main stages of heroin addiction:

A) Detoxing Heroin

The first stage in treatment is to detox. This involves weaning off the heroin gradually until no more heroin is needed to prevent withdrawal symptoms. The length of time this takes can vary from one person to the next. Drug therapies are often used for this to speed up the process and reduce the chances of relapsing during treatment.

Some common drug therapies for detoxing heroin:

1. Suboxone

Suboxone is a mixture of an opiate and naloxone (an opiate antidote). Suboxone is given to activate the opiate receptors in the same way as heroin but is given in gradually reduced doses.

To prevent abuse of this drug, manufacturers include naloxone — which spontaneously removes all opiates from the opiate receptors, effectively reversing the effects of the drug. If taken orally as prescribed, the naloxone has no effect. If the pill is crushed and injected or snorted, the naloxone immediately reverses the effects of the opioids and forces users into immediate withdrawal.

2. Methadone

Methadone is a long-lasting opioid with similar results as heroin. This drug works by activating the opioid receptors to alleviate symptoms of withdrawal. Just like suboxone, methadone doses are gradually decreased over time until it’s no longer needed to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. People use methadone because it only requires one dose for the entire day, thus eliminating a lot of the habits and routines around getting high for heroin users.

3. Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is considered a partial opioid agonist, meaning that it does some of the same effects as heroin and prescription painkillers, but doesn’t produce the same high. This provides a useful method of weaning off opioids over time.

4. Naltrexone

Naltrexone is used to treat both alcohol addiction and heroin addiction. It’s often sold under the names ReVia or Vivitrol. This drug is only given after detox has been completed, and is used to resist urges to take more heroin and relapse. It works by blocking the opioid receptors, as well as dopamine and serotonin. The drug has been shown to reduce heroin cravings 36], helping users to remain sober after finishing detox.

B) Rehabilitation Therapy

Once detox is finished, the treatment can truly begin. Many people are under the false impression that once detox is complete, the addiction is cured.

This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Relapse rates are high with heroin use, especially in those who didn’t go through proper rehabilitation to override habits and routines around their heroin use. Often, people will turn straight back to heroin use despite having gone through weeks of successful detox treatment.

To prevent relapse, time and effort need to go into rewiring the habits and lifestyle routines of those affected. There are both in-patient and outpatient programs designed to help ex-heroin addicts develop tools to curb cravings for the drug.

In-patient rehabilitation programs offer the most substantial support because patients get around the clock support from medical staff, and they get the added benefit of being separated from their normal routines. Eliminating all triggers, and giving ex-addicts a chance for personal contemplation, psychological counseling, support group sessions, and workshops go a long way in giving you the best chances of staying sober once the treatment comes to an end.

Experts agree that the more time you can spend in a rehab facility, the better the outcome in the long run.

C) Follow-Up Support & Therapy

Treatment doesn’t stop as soon as rehab is over. Maintaining sobriety takes a lot of hard work and attention. Most people that leave rehab will continue therapy through support groups like Narcotics Anonymous, and continued evaluation with councilors.

Heroin Overdose

Heroin is a powerful opiate drug — which also brings a higher risk of overdosing on the drug.

In 2017, over 15,000 people died from a heroin-related overdose in the United States [4]. This is a five-fold increase since 2010 [5]. It’s believed that the increase in prescription opiate addiction is one of the key factors for this rise in heroin overdose rates over the last decade.

As people become addicted to prescription medications, and the required dose increases, users are seeking stronger opiate effects in the form of street drugs such as heroin or fentanyl to feed their addiction.

Heroin overdose is characterized by a reduced breath rate, pinpoint pupils, and unconsciousness.

As the heroin interacts with the opioid receptors in the brain, one of the main side-effects is an inhibition in the respiratory center in the brain — responsible for controlling our unconscious breathing. As this part of the brain becomes inhibited during an overdose, the breath rate begins to slow dramatically. As this happens, the body starts to starve for oxygen.

In a matter of minutes without oxygen the cells throughout the body, including vital organs like the brain and heart will begin to die. This is ultimately the cause of death for people who overdose on heroin.

Other effects of the drug inhibit any feeling of concern while the overdose is occurring.

People who have survived heroin overdoses often report that while the overdose was happening, they were fully aware that they were dying. However, the euphoric and relaxing effects of the drug made them feel indifferent about it — they simply didn’t care that they were slowly fading into unconsciousness and would eventually die if they didn’t receive immediate medical attention.

Signs and Symptoms of a Heroin Overdose

- Pinpoint pupils

- Slowed or non-existent breathing

- Slowed heart rate

- Unconsciousness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Limp body

What to Do If Someone You Love Is Overdosing on Heroin

Heroin overdose is extremely deadly — immediate intervention is necessary to save the lives of anybody who may be affected.

The first line of defense for people overdosing on heroin is a drug called naloxone (Narcan).

This drug works by kicking all the opiates off the opioid receptors in the brain — reversing the effects of the overdose. It’s so strong in fact that a single dose of Narcan can force someone into withdrawal. Many people given this drug during an overdose will wake up almost immediately stone cold sober.

Even with Narcan nearby, emergency medical professionals should be called immediately. The Narcan only works for about 30 minutes before wearing off. If the opiates weren’t eliminated by this time, the overdose will begin happening all over again. Even if someone wakes up and appears normal after administering Narcan, they should still go to the hospital to be monitored and given follow up doses of Narcan as necessary.

References

- Kidd, S., Beattie, T., Brennan, S., Stephen, R., & Minns, R. (2009). Comparison of morphine concentration-time profiles following intravenous and intranasal diamorphine in children. Archives of disease in childhood, adc-2008.

- Robinson, S. L., Rowbotham, D. J., & Smith, G. (1991). Morphine compared with diamorphine: A comparison of dose requirements and side‐effects after hip surgery. Anaesthesia, 46(7), 538-540.

- Feng, Y., He, X., Yang, Y., Chao, D., H Lazarus, L., & Xia, Y. (2012). Current research on opioid receptor function. Current drug targets, 13(2), 230-246.

- Scholl, L., Seth, P., Kariisa, M., Wilson, N., & Baldwin, G. (2019). Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(5152), 1419.

- Hedegaard, H., Warner, M., & Miniño, A. M. (2017). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016.

- Gonzalez, J. P., & Brogden, R. N. (1988). Naltrexone. Drugs, 35(3), 192-213.